Felipe Ayres

Regardless if he knows it, Felipe Ayres is a fearless musical force, pouring his inquiring energy into his various sound creations without restraint. From soundtracks and music to foley and sound effects, Ayres applies his life lessons to bring amazing musical works to life using the instruments that speak to him at that very moment. Our video chat took place at the end of May. He in Curitiba, Brazil, and me in Taipei, Taiwan.

Interview conducted by Ryan Raffa

Ryan: Great to meet you!

Felipe: Very nice to meet you! Weird times, right? Weird times.

R: So very strange. How are things in Brazil?

F: Worse than ever, I guess. I don’t know if this is a word. Obscurantism? The denial of science. Denial of studies. We are living with people who believe that the earth is flat.

R: Have you been to the States?

F: Yeah, I went to SXSW in 2016 with my band. I have a band here, like a post-rock, instrumental band called ruído por milímetro. One of the members, he lives in Houston. That’s my only visit to the US. But I lived in England for almost 2 years. And I lived in Portugal for 6 months. In England, I lived in Sheffield, which is a very small city. An industrial city. And then in Manchester.

R: How was England?

F: I was just living a daily life. Working in a bar or something. I did take a really nice course in Manchester, which is ‘Audio Post Production’, because I wanted to come back to Brazil and start working with films. That was in 2014. So I came back [...] and just focused on dialogue editing, foley, sound effects, sound design. I still work with this.

I got a lot of jobs because of this post-production stuff. I would be working on a film, like dialogue, and they needed music. So, yeah, it would be me. I can do music as well.

[laughter]

And that kind of grew up. And now I have a lot more gigs on music for films.

R: So you went to England. Was that for fun? How did you end up in England?

F: I don’t think I would have the courage to do it by myself. I always wanted to do it. I always lived in this kind of bubble in here. Very afraid… because I’m very neurotic with these rules and bureaucracy.

R: You’re an artist. I understand you 1 million percent, my friend.

[laughter]

F: So you can imagine like you go to another country, and you have to do your taxes and stuff like this. You know that. You live in Taiwan. It’s very frightening.

I went with a girlfriend in 2011. She went for a Masters degree. But her Masters was kind of different. It was in 3 different countries. 6 months in Portugal. 1 year in England. And 6 months in Spain. I was not that young, but my mind was very young. I was 25, 26. It was some time ago. I couldn’t handle that very well. Living in a foreign country, have normal jobs and stuff. I was still an immigrant. We could work legally; we had the visas. But even so, we are always an immigrant.

R: You were outside.

F: Yeah, outside. Especially in England. Portugal was cool because there were a lot of Brazilians there. You know, we have this…

R: There’s a connection.

F: Right. But in England, it was very hard. It’s hard to get into the circles, you know? To make friends. The whole story is that it didn’t end up well. We split up in England, and I came back alone. But I came back with this new will to work on post-production and go on with my life. It was the wrong timing, I guess. Now it would be a lot better if I went to go live in another place. Because now I have my own place here. I have my three cats. I have all of these life responsibilities, and I’ve learned so much from it. Now things would be different.

R: I googled your name. I was like, ‘I want to see what I can find out about Felipe.’

[laughter]

F: Let me do that as well.

[laughter]

R: In a YouTube video from 2012, I see a very young Felipe. Well shaven, playing an acoustic guitar. And singing!

F: Ok.

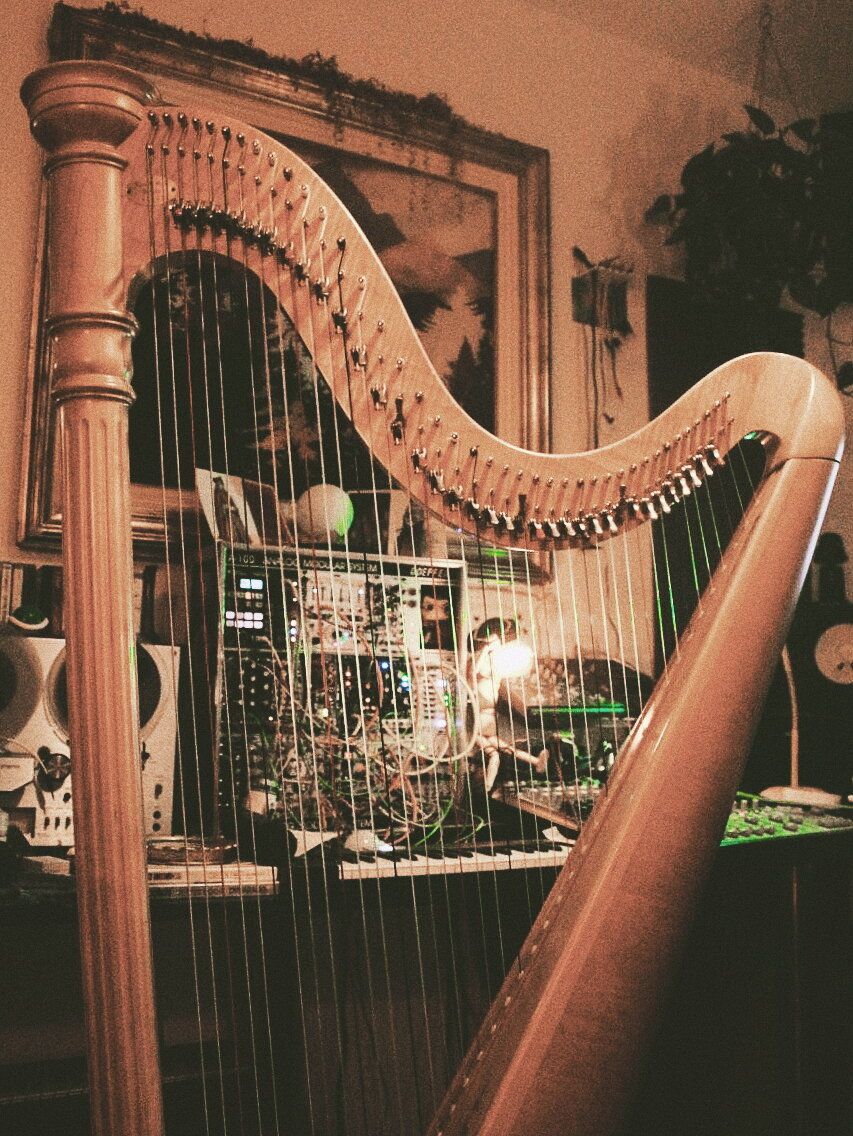

R: And it’s beautiful. It resonated with me immensely. On IG, I’ve seen you play the harp, and I see the gear behind you. And then you’re talking about post-production foley… I listened to your new record, Turvo, and then I listen to that acoustic guitar. I can hear it’s the same person. It speaks to this large swath of knowledge and passion that you have. Where is this coming from?

F: Do you want the long answer or short answer?

R: Did you just think ‘I want to play guitar’ and you just learn to play it? How do you approach all of this?

F: I think at one point when I knew that music, or sound in general, would be the things that I would be doing for the rest of my life, it is kind of scary. Because we live in a place where artists are not very well… rewarded. That’s the word. At some point I thought I would need to know a lot more than just playing an instrument. Or to do a mix. I knew that I would have to open the possibilities. Because if I don’t have a job with this one, I could have a job with that one. I had a lot of interests, but at first, it was mainly music. Like playing an instrument. So like 13 or 14 years old, I played guitar. Just for fun. Like a metalhead.

R: Did you play in bands all through that?

F: No. Just with friends rehearsing at home [...] I guess when I discovered the possibilities of the other instruments, like when I first heard Bjork when I was 17, and I started to get interested in the harp. It kind of changed my mind. ‘Ok I can do that. With the harp and electronics.’ And I can still play the classic acoustic guitar. I just brought things together. So I went to university. I learned how to teach music.

R: Like music and education?

F: Yeah. Because at that time, in 2004, I wanted to be a harpist. An orchestra harpist. I would have been one. But then I had this problem already. I love to learn instruments. Learning new instruments. I don’t play them very, very well, but I can play a little bit of something. So I wanted to focus myself on the harp. I studied harp a lot. And then all of a sudden, it didn’t make sense anymore. So I went to the guitar. And I went to the pedals. And at some point I got tired of all the wires, pedals, and bad circuits and stuff, and I said to myself, ‘I don’t want to work with wires anymore.’

[laughter]

It was a problem. In 2008, I put everything together. My first album I put the harp, I put piano, I put electronics, I put guitars, I put accordion. It was very mixed. And I used to go do that live. With Ableton Live, midi controllers, the guitar, the harp. It was nice, but it was very difficult. I didn’t get much from it.

R: You have to bring all that stuff on stage.

[laughter]

F: Yeah I know.

R: It’s not easy. I played in bands for like 15 years. Touring. Playing in New York, it’s like the show is fun, but people don’t see the before and after. They’re like, ‘hey, come party!’, and it’s like, ’No, I need to bring the drum kit back to the studio.’

F: Yeah, I was always alone. With all those wires. So in 2009, I got tired of it, and I got into finger-style guitar. Like maybe I saw Michael Hedges. He’s the biggest ones for me. I love it. At that point, I just listened to finger-style guitar music. For me, it’s all about what I am listening to at that point.

R: It’s like what catches your fascination. And you’re digging into that.

F: Yeah, I dive into it. As you said, when you listen to my guitar music and my modular music, you can hear it’s the same person. Inside of me, all of these phases, all of this time, all the things I went through, in the end, it’s always there. Even my Terminal album, which is my first modular album from 2018. It’s very industrial. It’s metal.

R: It even has techno moments in it.

F: Yeah, at one point I was listening to a lot of doom metal. So these very low guitar riffs are running in my head all the time. So sometimes it’s going to be in my music even now. It’s a part of who I am. With this new album, it’s all about very dense, slow textures. I’m very into chamber post-rock music, like A Winged Victory for the Sullen, or Rachels…

R: I’m a huge Rachel’s fan.

F: Oh, you know Rachel’s!

[laughter]

R: If I was to say my top 5 favorite albums of all-time...I’m really into that album Music for Egon Schiele.

F: Rachel Grimes on piano. Oh man, there’s not a lot of people that know Rachel’s. Rachel’s is amazing. I was never an electronic music listener. I was always listening to bands or artists that had electronic elements to it. Bjork. Radiohead. Neu-jazz bands like Xploding Plastix. They had elements of it. They were not mainly electronic. Rachel’s, for example, they’re a chamber band. They have drums. They have guitars. They have textures. So I always used the modular as an instrument inside of a chamber thing. I don’t see myself as an ‘electronic musician’. The modular is just a tool inside of these textures. For counterpoint to a violin. That’s how I approach it, I guess.

R: You’re using these tools, these elements around you, these instruments to express what it is you’re trying to say.

F: Yeah, exactly.

R: The new record, Turvo, is epic. I don’t know the best way to describe it but that’s my immediate response to it. Each song is interesting in its own way. It has a central theme with an arc, but each piece says something different. I love the variety. How did this record come about?

F: You’re totally right because this album was not all made this year. 3 or 4 tracks were from the past, and 4 of the tracks were more like totally modular based. Literally live takes from the modular. The other ones, they have piano, they have textures, they have drums. I put these together because, even if they are very different from each other, I felt they fit well together in a context.

R: When I hear you talk about the way you think about music or the way you’re approaching your work, it’s like you’re riding this wave of interest and passion. And you’re unafraid. Even if you say, ‘oh, i don’t know if I could live abroad’, you are fearless when it comes to music, or sound, or exploring those interests. Is that something you even think about or do you just do it? Like it doesn’t even register. As in, ‘Oh, I’m just going to learn to play the harp. I’ll learn the harp.’

[laughter]

Not everybody thinks it that way. Those are, I don’t want to say contradictory, but you have to say context is important here. That’s being fearless. Like just diving into this thing.

F: I think I’m not very aware of that. When I choose to do the stuff I do, I don’t feel fearless. I just do it. Like I never thought of it like a new challenge. It was all about the interest. When something gets me interested, I just go for it. Maybe I’m always searching for that place where I feel enlightened or something. I have this, I don’t know if it’s an issue, but it’s something I’m very aware of. Since we are all artists, and we live in this very difficult situation, one side of me is very pragmatic. I don’t know how to live with uncertainty. It’s very difficult for me to live if I don’t know if I’m going to have money to pay for rent or something, or if I’m going to have a job. So it’s like two things fighting all the time. I have all of these creative things to do, but I’m always putting myself down because I have all of these normal responsibilities as well. So maybe this feeling doesn’t let me be aware of the fearless element of it. Because I’m always concerned with what I’m doing. It’s never like, ‘oh my god, I’ve reached the target…

[laughter]

It’s always a feeling of uncertainty.

R: Yeah, as we become more technically advanced, the challenges become more and more.

F: Yeah. Sure. I’m kind of lucky that I’ve managed to find paying jobs inside of the music and sound world. So it’s nice that I can work in the same environment as the music. So I don’t blame myself that much for doing music or for spending time making videos or buying an instrument. I do blame myself a little bit because I spend too much money buying modules.

[laughter]

I think this is the good obsession in my life. Since I’m a music composer for films, and I have this classical background in music, I feel almost like a conductor in some way. I want to know a little bit of every instrument that I can because when I am going to sit and compose a piece for a film, or I’m going to orchestrate, or I’m going to do something, that knowledge is going to be good for the composition. That’s why it’s almost an obsession to learn new instruments. Sometimes it doesn’t work. Like I bought a viola, and it really demands a lot of time to play nicely.

[laughter]

R: Or to play the way you want to hear it. The sound you want hear and what’s coming out of the viola. There’s a gap there.

[laughter]

F: The gap in my life are the bow instruments. This is the gap in my life.

R: A few months back, I saw a story that you posted on Instagram. You were in a recording studio, and it looked like a string quartet. That was for television, right? What was your role in that situation? Are you performing as well? Are you the composer?

F: With this one, it’s a TV show. I edit podcasts; this is one of my jobs. This guy I edited podcasts for, he came up with a story like 3 years ago about a very well known case here where a child disappeared. In ’92. Very dark. A lot of politics. This case is very long, the longest case in Brazil history. After 30 years, this case is still going on. This friend of mine who does this podcast, he made a story about this one. A storytelling. He made the edits, and I made all the music for it. We never thought it would grow up the way it did. Now he has millions downloading it. It’s the biggest podcast in Brazil right now.

So the national TV, they are going to make a TV series from it. Like 8 episodes. This is my biggest project. I’m composing the music for the series. So we had the money to record strings for it. So I composed everything for it. I produced everything. At this moment, Dissolve in Sepia... you know Ramon?

R: Yes yes, most definitely.

F: He’s doing the mix and the masters for me. We work a lot together. On this story, I was conducting the players. I wrote the music for them, and I was in the studio conducting them. For them to really reproduce what I wanted.

This is a breakthrough for me. The soundtrack side of things. This is a huge thing for me, I guess. It’s very frightening as well. It’s always that uncertainty or insecurity. I don’t feel like I have everything under control. It’s like, ‘Oh my god, this is going to blow up.’

R: I always think that that’s a good thing. It’s like everyone experiences that. If you put yourself in that idea of the arena, everyone feels this. And it comes down to how you manage that. I always feel like that’s what drives me.

[laughter]

F: Yeah, I think that’s what drives us. We are driven by this feeling of, ‘We need to make it better. We need to make this good.’ Because we’re never satisfied with it. It brings anxiety, but in the end, it can be a good thing.

--

Turvo is out now on all digital platforms - a limited edition cassette is planned for mid-August. Follow us on Bandcamp for earliest notification.